Price Point 026: 7 Things That Help Movies Get Made

Or, missing them, that stop them from getting made

I think I have seen every movie about Hollywood and making movies from Sunset Blvd. to Sullivan’s Travels, Barton Fink, The Big Picture, Ed Wood, Blake Edward’s SOB, The Player, Once Upon a Time in Hollywood, Babylon and others.

A lot of these movies are about — “how do I get my movie made?”

And isn’t that the fundamental question we all want to know here in Hollywood?

I find that projects that aren’t being made tend to have one or more of 7 problems.

I am talking about story problems. I am not talking about the dominance of superhero films or theaters closing. And if you haven’t sent your script to anyone, you had a falling out with every studio head in town at last year’s WME Holidays Party, your wife left you and she had all the talent, or your agent hates you and your project, those are entirely separate issues.

It’s true that superhero and other big fantasy films dominate the marketplace, but there are original films being made and I’m focused on those. In the world we live in today, what are the things that help and, in their absence, hurt?

There has been a lot written on this subject but I will lay out how I think about it and try to highlight where I think conventional wisdom may be wrong.

1 NO STARRING ROLE

This is the most common issue.

When I say you don’t have a starring role, I don’t mean you don’t have a star attached or you don’t have a role with the most lines. I mean: there is not a role for a star — or someone who wants to be a star — to attach to.

A character may seem “well drawn” in that he or she seems true to life, desires things, and experiences emotions. But that is not enough for a star-making role.

What’s a star character?

Special. A star is somehow special. They have a special ability and charisma.

Goal. A star wants something. This is the same as having a problem. We want the star to get the thing. Getting the thing makes a big difference.

Push the action. A star makes the important things happen in the story.

Growth and change

Pay off in Full. A star has an ending. The ending resolves the character’s issues in a dramatic way. Obviously this is different in TV.

Be Special

The audience wants to watch someone special, even if they seem ordinary at first.

Every movie in a sense, is a superhero movie, even if the power isn’t very super and we have to reach deep inside to find it. There must in some sense be a special character. Even if they are just especially honest or insightful or funny or smart they have to somehow be special.

The “simplest” path here, simple just in terms of being true to life and not requiring a crazy leap of imagination, is to make them smart and funny. Of course, to write a smart and funny character that has to be your style.

Very commonly, you have your lead do the thing that makes them special very early on. So in My Darling Clementine, Henry Fonda, as Wyatt Earp, cleverly (but nonviolently) defuses a situation with a gunman by minute eleven. Now we know that he is special.

In Black Swan, Natalie Portman has the capability and the will to dance the Black Swan.

In Being There, Peter Sellers has the unusual gift of total naïveté and honesty.

These are not normal people. They are special.

If you don’t create a star — he or she is special, and wants something — it’s a problem for the actors and for the audience — because it’s fairly boring.

What about being “relatable”?

Pass. By “relatable,” people often mean “average.” That’s not helpful. Was Tony Soprano relatable? Is the guy in Billions relatable? Is Jennifer Coolidge in White Lotus relatable? Is Tom Cruise in Top Gun relatable? Is Bill Murray relatable in Lost in Translation as a globally famous movie star?

Be exceptional, unforgettable, and fun to play. Be charismatic.

These characters are relatable in that they want something. That’s enough. We can relate to wanting that thing. We admire something about them. We want them to get the thing. They don’t have to be “like us.” Lead characters do not have to be “normal.” And if they’re going to be unforgettable, star-making roles, in fact they can’t be. But they want something we relate to.

The toughest lead to create as a star role is the fairly normal person who isn’t sure what they want. Take Benjamin Brad in The Graduate. He’s a pretty normal guy home from college. Making that a compelling star role is great writing, and also, to be honest, great acting. Buck Henry, Mike Nichols and Dustin Hoffman made the character funny and compelling and gave him a heroic challenge — staying sane in a world that wasn’t making sense and finding a North Star. This kind of character is most often found in romances or romantic comedies, and once they are interested in their paramour they have a goal.

Have a Goal

This is not as complicated but we have to care about the problem and solving the problem has to make a meaningful difference to the star’s life.

There have to be “stakes.”

There usually has to be some passionate desire.

Lost in Translation immediately sets up Bill Murray as facing marital troubles and isolation. He has a goal, though it is somewhat implicit.

Oppression.

Dharmendra and Amitabh Bachchan — outlaws — are hired to protect a village from highwaymen in Sholay (1975).

Push the Action

A star cannot passively be buffeted by the forces of change. A star has ideas and drives change. The only time you can be driven by a random force is in the very beginning where the inciting incident sets the world off kilter. After that, we are watching the star contend with the world by making choices.

Grow and Change

Bad outcomes should force the protagonist to reach deep inside, come to conclusions, and … change. They have to make a decision that this quality about themselves, this choice, is the right choice, and that other path is wrong. They have to grow up or shed their skin.

Pay It Off In Full

Act 3 must resolve Act 1. And whatever conflict, rivalry, aspiration, etc. has been established, it must be resolved in act three. Take a point of view. Don’t lose the thread of the story. Don’t be postmodern.

If there is one film I would encourage you to see that you probably haven’t seen, it is Pawel Pawlikowski’s Cold War (2018). This brilliant film was nominated for Best Foreign Film and Pawlikowski won Best Director at Cannes. The story is about a couple in love who pursue each other and their musical ambitions in Europe during the Cold War. Although there are twists and turns and other characters in the drama, the third act laser focuses on their goals and pays off everything they have wanted, all of their best qualities and all of their worst qualities in a devastating ending. People want the end to be really sad or really funny or really triumphant, but they want it to be really something — and that requires paying off what you have set up.

We had a movie once called Wonderstruck (2017) directed by Todd Haynes from the book by Brian Selznick. In Wonderstruck, the problem of the movie was really created early on when Julianne Moore’s character’s husband died. That’s what set the world of the film off kilter. The rest of the film followed from that. Which is how inciting incidents work. It was such a beautiful and cinematic film with a complex narrative. It had beautiful shots. It had scenes. It had sequences. But Lilian Mayhew’s (Julianne Moore’s character) wound was never healed or her story resolved. There was a broad resolution, but her story with her husband was almost treated as backstory once it happened. Act three closed out the story of her son and to some extent the broader family. But I think it wasn’t enough. The architecture of the story must tie back to causation and must be symmetrical with act one. I think we made a little architectural error here and the film wasn’t everything it might have been.

I think this is essentially the issue in Babylon (2022), too. There are sequences in that film that should go in the movie museum. But no character was really the lead or had a strong third act resolution. I really admire Damien Chazelle but he once said in an interview that Hollywood was really the lead of the film. I’d say that’s a no-no.

Ok. Now we have four things.

We have a special character with an important goal. The protagonist drives the story. They grow and change. The payoff resolves the story completely.

When someone puts the script down they should say “well, that’s a career making role for someone,” not “that’s a well drawn and honest character.” people get paid to create stars. Well drawn and honest characters are free.

This is worth spending time on.

2 DID YOU LAUGH OR CRY?

If you didn’t laugh or cry at all writing the script, why am I going to? It has to have feelings and they have to feel real. What I really mean here is that the story has to be honest and it cannot be melodramatic. A lot of scripts that don’t quite make it feel “professional” in that technically everything works, the turns are in the right place, people want things, etc., but they do not feel deeply felt. You can’t fake it.

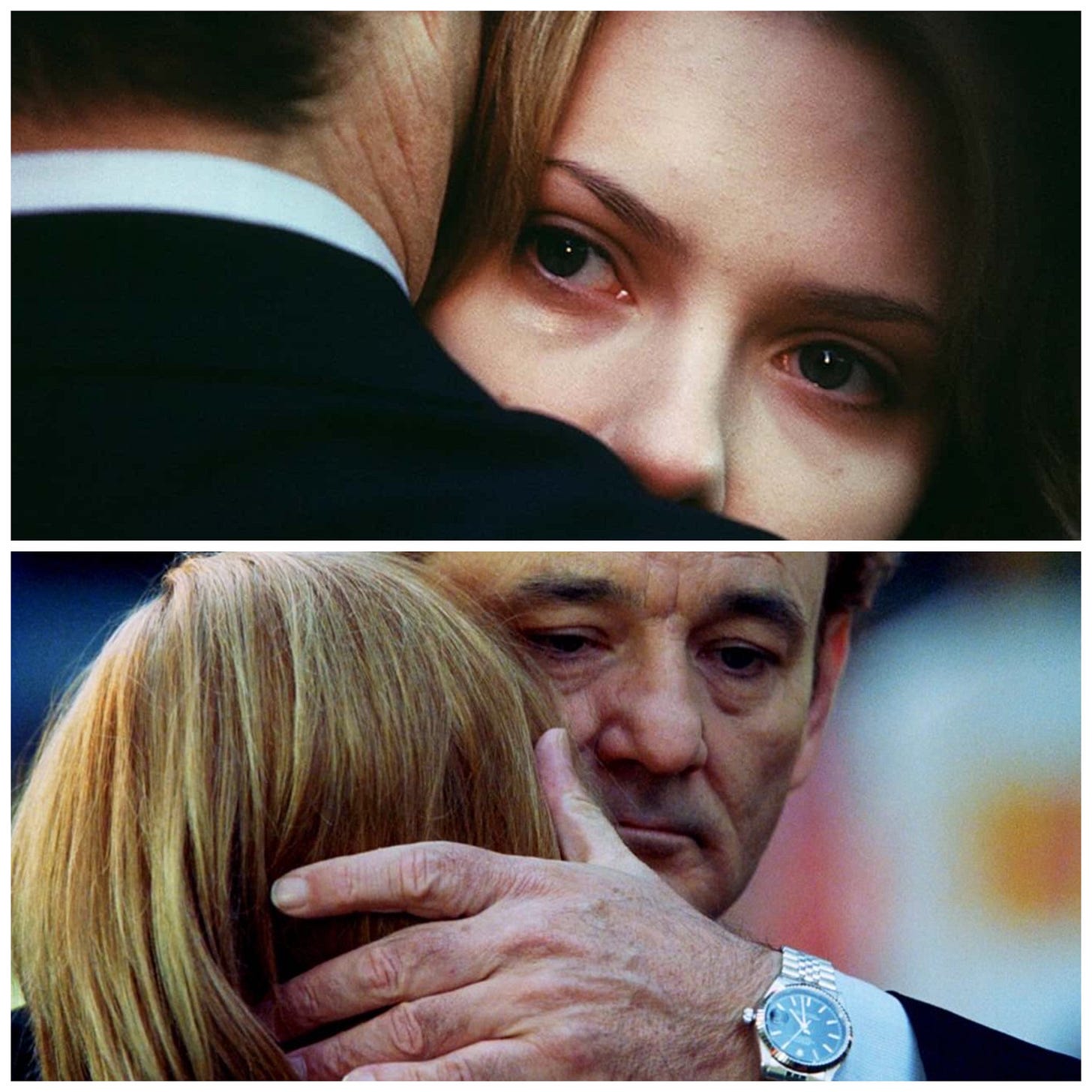

My theory on awards is that it helps to be what I call “tragically beautiful.” It’s the Academy’s favorite flavor.

3 MATCH STAR AND VILLAIN

The lead and the antagonist must raise each other to their greatest moments. They have to be a good match. If two people are fencing and one is incompetent, it’s short and dull. Julia Roberts and Jude Law were brilliant fencers in Closer (2004).

Dan: You’ve ruined my life.

Anna: You’ll get over it.

4 HAVE MULTIPLE GOOD IDEAS

It’s not unusual to find films with an interesting premise and first act but then nothing very inventive happens in the rest of the movie. It’s just serviceably executed from there. Really great movies usually have multiple fun ideas one after the other.

Think of a movie as 8 x 14 page chapters. Each one should be a banger. To go old school, a reel of film is about 11 minutes. Think of each reel as a chapter and make sure each chapter gives us something new and exciting.

5 BE CINEMATIC

This is a bigger issue than it used to be. “People talking in rooms” movies are being relegated to streaming. I’m not saying you have to put everyone in a spaceship, but try to make it somehow a large experience.

6 HAVE A LOOK AND A TONE

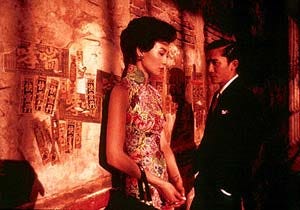

When you are inside the world of the film, it should not feel just like the world of any other film. The tone, the style, the look…make it unique.

Film is a visual medium. It helps to have a look. I would argue that the look is not independent of the idea such that you could just hire a DP and get a “look.” The look comes from and supports the idea. I could paste a thousand images here but I will go with one.

Garry Marshall used to say that every show should have someone who speaks like no one else on television. Having a dialogue style and tone that brings us into a distinctive world and that shows discipline in creating a world helps.

7 LOVE AND DEATH

This is less a requirement and more of a bonus opportunity if it can fit in. People care about violence and death. They care about love and procreation. Both help grab the audience’s attention. You can go without it, but I always love a good wedding. If you have four, you can’t lose!

If you have all those, you probably have a banger of a movie!

OTHER ISSUES

It’s cheap – Sometimes people wonder why their movie isn’t getting made when it only costs x (say $1 million).

This is not how the economics of film work. Let’s say you’re greenlighting movies. You have an annual budget of $500 million. Two things. First you want the average return of each of your 500 million dollars to be as high as possible. So what is the highest probability investment? Generally it is not going to be the $1 million film. If it’s that cheap, it means no one wanted to be in it and you’re never taking the camera outside. Come back when it costs $25 million!

Second, it is axiomatic that any film generates a certain minimum number of crises and plain old supervision. To get on the slate, a film has to be big enough to justify the overhead.

Why now? - Often people will ask about a TV show or movie, “why now”? Generally I disapprove of this question because execs tend to think of the question as “what does this have to do with what I am reading in the news?” That’s such a bad way to think about it. Remember – the movie is coming out in two years. You want it to be about what’s in the news today?? Generally, the reason to do it now is that the script is good and available, the director is great and available and the cast are great and available. Now! There have been many period titles that have nothing to do with “why now.” So stop asking.

But there is one version of this that I do approve of, which is the positive version – where you can ask the question but people can only win points with their answer, they can’t lose points. So if there is something about the show or the cast that really is going to make it stand out in today’s world, something that puts it on the edge, let’s hear it.

What about theme or motif? Some people are really into theme. My grandfather was. But by and large I don’t know any writers who use that explicitly very much. Obviously you can deduce a theme in the end, but developing theme first as suggested by Lajos Egri in The Art of Dramatic Writing and then writing to the theme seems like writing an essay.

Thanks for reading. I hope it helps you or spurs discussion.

Coming soon … Why do bad movies get made?

I’m not involved in the filmed Industry. But found this very interesting. Thank you. What would be your three top Action movies that tick these boxes?

Love this. Interestingly enough screenwriter groups are advising everyone write to a budget. Get your costs down to 2 million to sell their spec script.