Price Point 023: Will scale determine the winner in subscription video?

Actually, there are more important things

“Can you build a big business without [intellectual property] and without a library? We just did.”

- Ted Sarandos in a recent interview with Lucas Shaw

Does scale inevitably determine the winners in Big Hollywood, in the race to be one of the finalists in subscription video (SVOD) such that you would always prefer to hold the bigger asset?

Let’s take a look.

My thesis is that we are moving from the Scale Phase, where SVOD competitors were shooting for scale, into the Brand Phase where competitors will try to define themselves more sharply, culturally, for specific target audiences and will include content in their services only when it serves their specific brand story. The audiences SVOD services choose to focus on will have to be broad but specific enough to be differentiable; in any case, the pretense that the audience is “everyone,” for most competitors, will increasingly have to be abandoned and selection at SVOD services will have to become more intentional.

With any retail effort you can try to be Walmart or you can be a boutique. That is, you can offer everything or you can offer a specific thing to a specific group. Only Comcast as a whole and Netflix now are credibly the “Walmarts” of television. And Netflix is much cheaper. In the US, cord cutting and the shift to streaming are gaining momentum. Now only 61% of US HHs have pay TV.

Spending $17B per year and offering everything from Dahmer to Cowboy Bebop to British Bakeoff to Wednesday to World War II in Colour, Netflix’s positioning appears to be against basic cable — there is something for everyone. But Disney and MLB, for example, are not offering everything. They are specific. You subscribe to them because you want Disney’s brand of magical, larger than life family friendly programming or because you like baseball.

Other than Netflix and Disney, most competitors are pursuing a K-Mart strategy, which is “Walmart but smaller” or the Everything Store … but not really with everything. That’s not a great strategy. People want to know — and be excited about — what they’re buying. Meanwhile, packing these services with as much content as possible has led to overstrained P&L’s. We have recently seen, for example, Warner Bros. Discovery pulling non-core content off their service to improve the economic health of the service.

As people tailor their services and shrink them down, to find success they will have to prune them in one direction or another — toward this audience or that. Instead of being scale driven, the services will still be large-scale but will increasingly be specific and brand driven.

So what is the importance of corporate scale and to what extent will it determine success going forward as we evolve into the Brand Stage of this competition?

What is scale? There are two relevant aspects.

You have a big library of shows and movies. This breaks down into two parts: the IP (the rights) and the shows themselves.

You have a big budget, which usually comes from having a lot of customers.

TV IP

This is a good month for series reboots of earlier series and IP. We have The Last of Us, Wednesday, and That 90s Show all starting strong. And we will see if they hang in there to become some of the most impactful shows for their networks.

I would note that none of those shows are owned by the networks that air them so they aren’t necessarily arguments for the value to an SVOD service of owning your own library. They might be arguments for the proposition that libraries have value in general, but not for the idea that scale wins.

In any case, I would argue that originals (including shows based on IP but not on earlier shows) are still much more important than reboots. What are the most important recurring series now on TV? We can quibble but I will throw these out —

Yellowstone and its variants

House of Dragons

Mandalorian, et al.

White Lotus

Succession

Squid Game

Bridgerton

Rings of Power

These are overwhelmingly not reboots of previous shows. House is a sort of sequel but you could also see it as merely a continuation of Game of Thrones. Going back in time, Sopranos, Breaking Bad, and the overwhelming majority of successful TV shows of all time are not reboots.

What matters in television is quality execution. Which means talent. Which means money. Money matters. Being good at programming matters. Having a library of rights is occasionally helpful but not more than that (maybe more than that if you’re Disney).

TV AND FILM LIBRARY

Library films and shows (your actual produced shows from the past) primarily help with subscriber retention. It gives people something to watch between major new events. So it increases visits per month and hours per month, cutting down subscriber churn and putting less pressure on your originals and on marketing to deliver new signups.

Having a weak library is like playing bad defense in baseball — it puts more pressure on your offense to score.

A lot of library content — unless it is The Office or Parks and Rec — is fungible. That is, you have to have something, but it doesn’t have to be a specific thing. Netflix does really well with British Bakeoff and World War II in Colour. And every SVOD player we are talking about has some library or licenses library.

I anticipate that we will see more, not less, cross-licensing of library going forward as services refine the personality and identity of their service and try to align their catalogue with their own unique brand and target audience. So even if you have a smaller library, I expect you should be able to license what you need.

If library were the key to this game, Peacock would be doing much better. And I will note that as library content was removed from Netflix by licensors (Disney, NBC Universal series), the impact on Netflix wasn’t dramatic. So the Moneyball answer I think is — you need library but it won’t win the game for you and so long as you can fund the category and license from third parties, you’ll be fine.

I think that a high percent of library content will wind up on ad-supported networks and tiers.

MOVIE IP

Library IP has its greatest impact in movies where franchises like the MCU or Fast and Furious or Avatar deliver reliably. Of the top ten movies each year, most are part of some franchise. So depending on the nature of your library, this can range from very helpful to somewhat helpful.

Movies matter for attracting subscription customers. But they tend not to matter quite as much as recurring series. So a library will contribute something here.

All things being equal, having a library is helpful. In some cases where your programming is really designed around franchises (Disney), it’s essential. Otherwise, it’s just helpful. Money and talent matter more.

Bottom line, taking everything into account, having a library is helpful. If you’re Disney, it is of the essence. They should almost be analyzed in their own category. But in general, while the scale of your library will make things easier at the margins, there are more important things.

So would you buy Paramount ($15B) or Lionsgate/Starz ($1.5B) if you could?

This is a theoretical exercise to illustrate this point — would you buy Paramount1 or Starz if your goal is to wind up with one of the three biggest services in 2031? Assume the cable business is headed south,2 which is why Paramount’s price to earnings ratio is 5 vs. the S&P 500 mean of 15.99. (Note that the prices above are just the market caps of the public equity and actual purchase prices would be much higher.)

I’d say you would prefer Paramount straight up, of course, but if you could have a higher budget at Starz, my point is that despite the scale, Starz could outgrow Paramount+ over time. So instead of buying an asset for $15B, you buy the other asset for $1.5B with money set aside for anticipated content investment and then you grind them down with more and better originals. Because if it is really about originals at the end of the day, and it’s really about executing against a specific brand identity, then you just aren’t getting enough for the incremental $13.5B that is going to position you for victory in 2031.

With respect to the money, Starz spends about $1B per year on programming whereas Paramount+ I believe spends about $3B. (Netflix spends $17B.)3 Paramount is planning to ramp up to $5B which is still well below Netflix, Amazon and HBO. So at Starz you would crank the spend up to $8B-$10B over a few years. You can’t go from $1B to $10B in a year or you will be making every bad project in Hollywood. But over a few years. This spending increase will come ahead of your subscriber increase necessarily so you will have to be prepared to lose money for a minute. However, if you wind up in the end with 100MM global subs valued at $500 each (Netflix is valued at $700/sub), that’s a $50B company. Today Starz on its own is worth maybe $2.5B. It’s worth losing $10B to grow it from $2.5B to $50B. (You would only hit those numbers if you targeted a big underserved audience, but I think that audience is out there.)

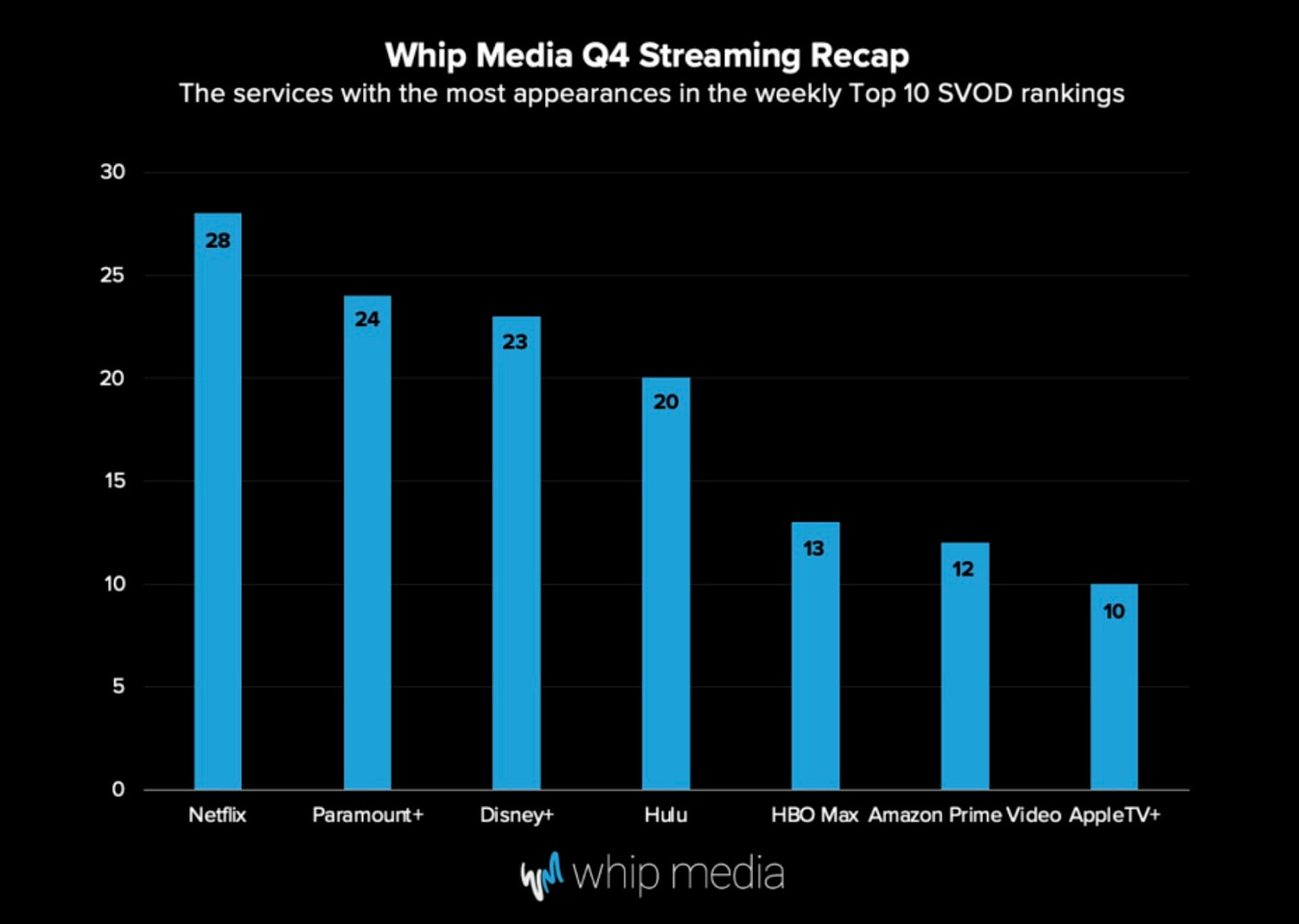

In this process it is worth noting that not all dollars are equal. They are not all spent with equal efficiency. The team matters. We see Paramount+ recently giving Netflix a run for its money despite spending perhaps 1/6th as much as its monolithic competitor.

This is because Yellowstone, Tulsa King, 1923 and the Taylor Sheridan/101 Studios franchise is hitting it out of the park.

In general, the strategy would be threefold:

Develop a specific personality and brand, focus on a (big) target audience

Focus on talent (whether they are super established or beginning or at the peak of their career or not)

Don’t put all your eggs in one basket

At Amazon we went through a brief period toward the end where we could really only get behind fantasy and sci-fi shows. Some talent-driven, non-genre shows that we were not able to do:

Yellowstone (Taylor Sheridan and Kevin Costner)

Morning Show (Jennifer Aniston and Reese Witherspoon)

Kominsky Method (Michael Douglas and Chuck Lorre)

And some that wound up not getting made by anyone.

Rings of Power presumably cost the equivalent of several original shows. I could argue that the “huge bet on IP” strategy is too risky and the network would have been better off just continuing to greenlight the best shows we could find. I’d say the Yellowstone franchise or Yellowstone plus Morning plus Kominsky would be more valuable than Rings of Power now. So in general I don’t love massive bets that become your whole lineup. What matters isn’t your number of shows or your budget or how big the battle scenes are. What matters is having shows that people love. And delivering quality on a regular cadence to the same group (your target audience). Statistically, shows with IMDb ratings above 8 tend to drive subscription gains and shows with IMDb ratings below 7 tend to drive losses.4

Yellowstone: 8.7

Marvelous Mrs. Maisel: 8.7

Fleabag: 8.7

The Boys: 8.7

Morning Show: 8.3

Kominsky: 8.2

Rings of Power: 6.9.

The most important thing in this theoretical race between Paramount and Starz would be having a good head of programming. Also, if you’re in luck, some of the programmers you’re competing with won’t be great. If you can wish upon a lucky star that your competitor will keep pumping billions into shows pulling 7.0’s on IMDb, you should do that. Right now, HBO has a strong programming team. Maybe Paramount, too. It’s a bit early to say, but I did like The Offer.

In stock car racing, all you need is a car and gas and you can win. In subscription video, especially in this emerging phase, it will be understanding the new nature of the competition, knowing who your customer is, defining what your brand is, and bringing that brand into being with appropriate and compelling programming. Everyone has a long way to go. But this is not strictly scale-driven. What you need is a platform, talent, and money.

What is the upshot of all this?

All platforms have a shot to define themselves and grow.

We do not live in a Calvinist universe where some are predestined to succeed or fail. Some will make the most of this and some won’t. It depends on talent.

The medium term defensible characteristic of these businesses is going to be the specific brand loyalty they earn by speaking directly to their customers, just as Disney has brand loyalty today. Some of them, where they gain very large audiences, will in time develop scale moats.

The only way this winds up being less true is if there is truly massive consolidation such that a peer to Netflix is created that can offer another Walmart of TV. This would require some merger of Peacock/NBC, Paramount/CBS and WBD/HBO. I don’t expect that.

PS What’s the phase after Branding? Bundling. A topic for another day.

Why did I choose Paramount? No reason. Starz is small. Paramount is bigger. So it’s an interesting comparison. But Paramount is not so big, like Comcast, that buying them is out of the question.

One interesting theoretical question for another day is whether this accelerates because cable programmer budgets decline, eroding the product; slows because there is a core group who like the product; or reverses because pay TV entities improve the on demand experience.

This isn’t strictly apples to apples because Netflix is devoting a much larger share to its international program.

It occurs to me that Netflix could be the one exception to this since they aren’t so much trying to offer a premium supplement to television, they are trying to supplant basic television. So whereas HBO might have said “It’s not TV. It’s HBO,” Netflix might say “It’s TV — it’s Netflix!” So could they be uniquely exempt from the 8.0 rule?