People have been worrying about Hollywood since its inception, like America’s beautiful but sickly child, but they seem extra worried now — for studios, for creators and for customers. Which concerns are real, and: as the walls close in, what can possibly save Hollywood from a grisly fate?

The woes

Most SVOD services are just barely breaking even, if that; both profitability and growth are under pressure. Meanwhile, the miraculous cash cow of pay TV seems to be dying and everyone wants to or is spinning out cable assets into a third party “Bad Co.”

Movies aren’t doing very well at the box office.

Quality certainly doesn’t seem to be up, and some genres seem quite unjustly shunned (comedy).

A few years ago, there were a lot of sequels but now it’s truly nuts.

Creators (writers, directors, producers) feel they don’t get the upside they used to get.

All these dumb kids are on #!€}#! TikTok and seem to be less interested in film than they used to be.

AI threatens us all!

No one can finance an indie film; streamers cared about them for a minute and then hastily dropped them off on the church steps.

Consolidation of the business puts decisions in the hands of fewer people than ever.

Now that producing has become some sort of nonprofit dilettante sideline for trust fund kids, the exec career path sort of lacks a “career path.” (In fact, other than being a lawyer maybe, does any role in showbiz feel stable and promising?)

I think people are pretty familiar with these problems so I’ll save you (and me) the 10,000 words spent substantiating every one. But I will note that “survive until ‘25” has become “‘25 box office is down 11% versus ‘24 and is expected to wind up down 17% vs the average of the last three pre-pandemic years.” Cool.

What happened in Hollywood over the past ten to fifteen years is that everyone saw the subscription video train coming. And they ultimately, very slowly, decided that they needed to be on that train. That beautiful, perfect train needed to be part of their growth story. So everyone hopped in with their own service. But. It turned out that most of them, well, all of them I suppose, didn’t quite have a sufficiently robust selection — didn’t have “31 flavors,” if you will — to offer customers. They just had a smattering of this and that, which didn’t really blow everyone away, and so pricing and subscription numbers were lower than hoped. But the SVOD frenzy was so great that they optimized their entire business for SVOD, limiting for example theatrical exclusive windows or foregoing theatrical entirely.

Meanwhile, the ubiquity of the services and the more or less immediate availability of movies on demand killed or seriously damaged four things: cable, DVD, syndication, and theatrical. Netflix was optimizing everything for the service, so everyone followed that approach. But not only were those critical revenue sources diminished, but the business dynamic for creators was somewhat changed. Compensation used to be highly variable. A big hit movie would drive a lot of DVD sales attributable specifically to that film and key creators would get a big cut. But in a streaming world, most MAGR definitions (Modified Adjusted Gross Receipts — the contractual definitions of what “profit” means and how you might participate in it) changed from being an uncapped percent of a waterfall of various revenue sources to essentially a table that would yield bonuses under defined circumstances. I shouldn’t complain because Dan Scharf and I got that rolling at Amazon, but I’m just telling you what happened. So the difference here was that instead of having uncapped upside so that if you made Star Wars you could walk away a billionaire, you would now get a bonus. It had the advantage of simplicity and clarity, but “Montecito money” was off the table. Many creators do not like this.

On to the solutions.

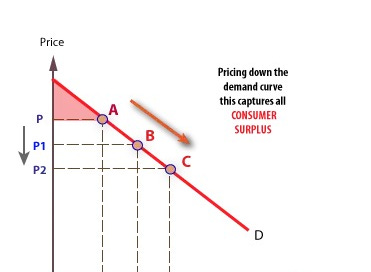

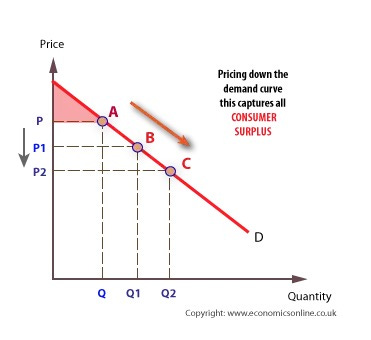

I’m going to lay out some possible solutions that range from small adjustments to major changes. Some of these ideas revolve around the same basic notion which is that the pricing and availability of film and TV seems to be capturing a smaller share of customer surplus than the old windowing system that went from theatrical to DVD to cable pay one to cable pay two and to TV syndication. The idea with the old, good, system is that the people who are most excited about the product and want to see it early, or own it, contribute more. People who are more indifferent (the product offers them less “surplus”), can catch it for free on TBS in a couple years. Price and timing discrimination, like charging higher prices for great seats at the theater, is how you capture more customer surplus from keen customers who can afford to pay, as seen in this chart.

But if you just have one window, which is subscription, you don’t price discriminate at all. You could be Bill Gates and Wicked could be your favorite movie that you’d pay anything to see as soon as possible and to own, and you want the special Blu-Ray sku at Target with the witch’s hat included, but in a subscription format Bill winds up paying the exact same as everyone else and getting the exact same product. In business this is usually called “leaving money on the table.”

There is a question underlying a lot of this which is: can we walk some of this back? Or has a genie been let out of a bottle once and for all?

You might say oh well I don’t care if the big companies make money. That’s their problem and it doesn’t affect me. But, no, my friend. Because when the big companies make money, that trickles down to everyone, from agents to the talent to the valet parkers at Hinoki and the Bird. There is no doing well if the studios don’t do well.

WINDOWS

I think that, in all the excitement, mistakes have been made. Would it be possible to create more of an exclusivity window around theatrical and would this improve theatrical grosses? I don’t know why not. There used to be a 90 day window. Theatrical results were stronger. Now we have a variable but much shorter window and results are worse. All the other variables have pretty much remained constant so this experiment is roughly “ceteris paribus” as the economists say. Why not try it? And indeed people are discussing a 45 day window now. I endorse this effort.

I will note that when we launched Amazon Studios movies, we put all our films into theatrical with an exclusive window and it seemed to help drive awareness and demand, which was the reason for doing it. For example, Manchester by the Sea grossed $48M in 2016. Last year, Anora grossed $20M and The Brutalist grossed $16M. I liked Manchester, but part of that is windows.

Secondly, is there any way, through windows or otherwise, that some value can be brought back into the ownership model that used to be represented by DVD and Blu-Ray? I’d like this to be the case, but I’m less bullish. If you look at music, it seems that once people have an all you can eat subscription with everything forever, then people stop caring about ownership. However, what about the windows on the backend, the “forever” part? Should it not be forever? How long should a movie be on an SVOD service? What if it was just six months or a year? What if people did not have a sense that once a movie was on SVOD it was permanently on SVOD? Would purchase have more attraction? Or would it drive up piracy to an unacceptable degree? I’m not sure the allure of ownership can be restored but certainly a lot of money has been lost as it has faded away.

OWNERSHIP/FIN SYN

From 1970 to 1993, networks could not own their TV shows. There were two benefits to this in theory. First, it allowed a more competitive and more diverse content ecosystem. Also, an open system should yield better shows because networks wouldn’t favor their shows over third party shows — all shows would have the same shot.

What if streamers could not own shows and could not license them for more than three seasons at a time?

In that case, the future seasons of hit shows would essentially be up for auction after season three. So Bridgerton, Netflix’s most watched show, would be soliciting offers now for the next three seasons. What do you think they’d get? Well, they’d capture a lot of the surplus they create. Let’s say an episode costs $8 million. Could they get $20 million per episode for ten episodes per season for three seasons? Who knows? But we’d certainly be closer to an open, uncapped comp system than we are now. (And a similar dynamic would apply to future licensing of past produced seasons.)

A STEAMER FOR INDIES

Indie films are somewhat neglected today. Maybe it’s algorithmically justified, but I watch indie movies and I find I don’t come across them. I don’t know where they are. And now we see that there are only 15 films per year that are scripted original non-horror films with a budget under $35M whereas in 2019 there were 33 (details here). This market is getting smaller partly because (I think) the films are mishandled in the massive bin of subscription video services. I think there would be an audience out there for an “indie streamer,” by which I mean a streamer with indie films plus original series plus some of whatever Hollywood is not doing, like comedy. This would benefit this category and the customers for this category. I wrote about this here.

A DECENTRALIZED STREAMING UTILITY

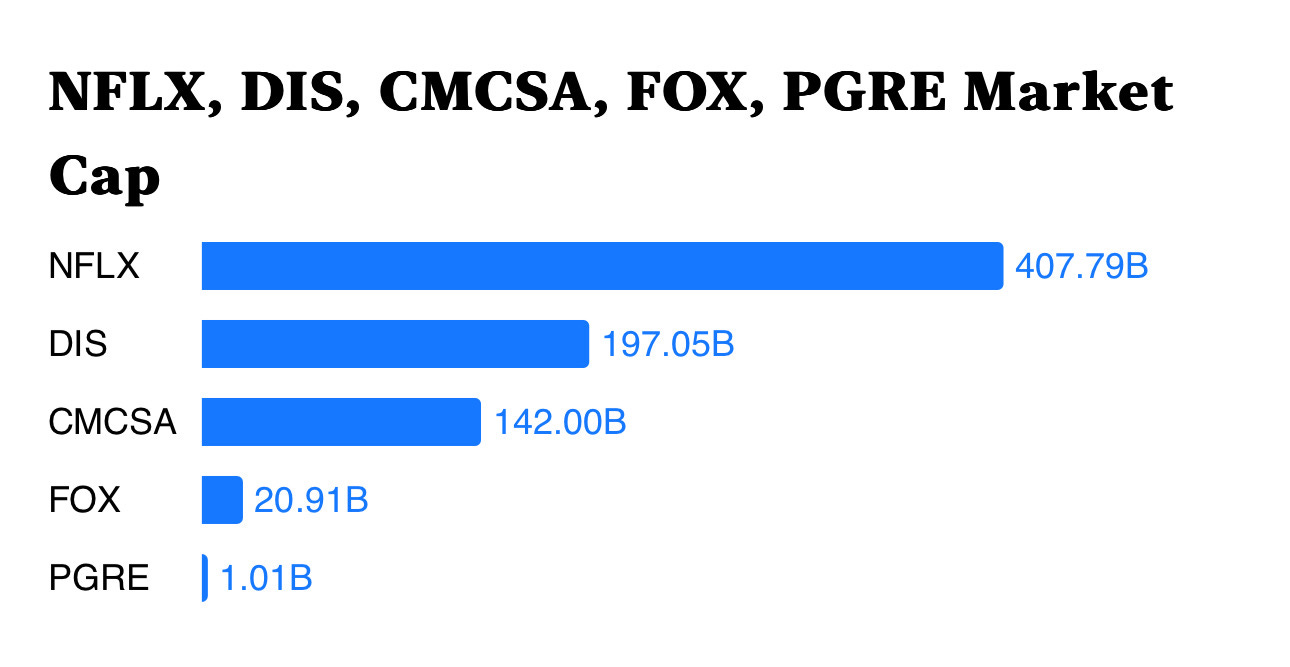

As discussed here, the ideal design for streaming would be a streamer that is truly just an open and transparent decentralized censorship resistant protocol out there living in space, on servers just unstoppable running via code and an economy of tokens. Anyone could add a show or movie to this system which would transparently distribute revenues after taking a modest share. Windowing would be up to content owners. Filmmakers could independently finance their projects on a global open market, which I suspect would leave them with greater upside and control. Instead of the whole industry revolving around one big streamer P&L and one concentrated leadership team, many studios would experiment and thrive — more like in the video game business. Note how currently one company is capturing most of the value in the industry.

MERGERS

Should Warner Bros and Paramount merge to scale up against Netflix? Or Universal and Warner Bros.? There was a lot of enthusiasm for this idea a year ago or so with the hope that one day the government would become more flexible and allow people to merge again. But the perspective of the administration remains unclear and plenty of ambiguity remains. As much as I think Warner Bros and Paramount should merge, I’ve become skeptical that this will occur. It’s a lot to commit to if you don’t know that the government will let you do it in the end. In theory, if it created a healthier streamer, that would be a positive development, but I wouldn’t count on it. Who would this be good for anyway? In theory the studios. Probably neutral to slightly positive for everyone else though some would say get having 6 buyers become 5 would not be helpful. It’s more likely that services will be bundled so you get them all at one combined price.

OPEN DEVELOPMENT

I think one thing that will happen which will benefit creators is that people will do more development and testing ideas in public. That is, today, you could throw an idea out there on X or threads or whatever and see what people think. But now you could fairly easily include a poster and with some effort you could include a trailer. With some positive initial feedback, you could create a number of shorts exploring your movie or series idea. If these get traction, you, whether you have an agent or not, could get a lot of attention from financiers or studios. I can’t imagine this not happening.

THE INFINITE TORRENT SCENARIO

In the looming tomorrow, AI will create increasingly watchable content, increasingly indistinguishable from “real” content, and increasingly good. It will conjure worlds indistinguishable from those born of human imagination. These silicon muses will divine concepts, weave narratives, and birth scripts with the casual efficiency of a god bored on Sunday. Picture a vast, relentless hive-mind summoning and testing countless pilots, each one probing our collective consciousness, each one learning from our most minute reactions. When a concept catches fire in our neural pathways—behold!—one hundred episodes materialize instantly, perfectly calibrated to our dopamine receptors.

And these offerings will not be merely adequate. After the system update, they will be sublime, exquisite in their calculated appeal—digital chimeras engineered to ignite precisely the right neurons at precisely the right moments. Imagine an endless cascade of narrative nectar, a bottomless well of content tailored not just to demographics but to individual psyches, each story morphing in real-time to the viewer's unconscious desires. Your entertainment will know you better than you know yourself.

As the algorithm perfects its dark arts, consumers will surrender to personalized phantasmagorias beamed directly into their cerebral cortexes through gossamer theater glasses they'll forget they're wearing. Reality itself will become the unwelcome interruption to these bespoke fever dreams. Each viewer adrift in their own custom universe, the shared cultural experience of storytelling atomized into billions of solitary hallucinations.

What do we do about that? I have no idea!

CONCLUSION

I feel like “Hollywood” used to have a cool vibe, like a Laurel Canyon summer house party with original music suffused with the idea that we’re about to create the next big thing. But now — and I don’t think it’s just me — doesn’t Hollywood have more of a tense, low key Hunger Games vibe? This may be a consequence of all the other factors, all the woes, of the walls closing in on Han and Leia at last, of the stern and judgmental culture, of the politicization of everything, of the feast or famine nature of the business, but somehow it has gotten a lot worse over the past ten to fifteen years, and this has to be repaired. How can this be repaired? Maybe the whole situation has to be repaired? I don’t know. But I think this is part of the problem. People are tense.

As Fitzgerald wrote, "Not half a dozen men have ever been able to keep the whole equation of pictures in their heads." The equation is changing, and not always in a good way. The industry must be open to creative changes — some tech-enabled, others legislative — to get good results for creators, studios and customers.

RP

I think this (sort of) qualifies for my "If I ran a studio" FilmStack challenge, Roy, even if you did not submit it... Great collection when paired with your prior post. I wish we could roll back time...

This is a great overview that few analysts could write in any industry.

Roy Price is the #1 thought leader in an industry that needs new thinking.

To fully appreciate the potential, think about the upside of getting into the film and TV business compared to almost every other industry.

Investment creators and promoters on Wall Street are out of ideas.

The problem with Hollywood is the long history of investors being exploited in multiple ways.

New business formulas that treat all the players fairly will emerge.