(after Luigi Pirandello’s Henry IV)

"Grosse Point Blank pulled three-point-one for the weekend," said Craig, adjusting his tie as he scrolled through an Excel spreadsheet on a bulky Dell desktop. "Down thirty-five percent from last weekend. Not terrible for week three."

Dianne Kim entered, immaculate in a tailored pantsuit. "The Dante's Peak comparisons?"

"All prepared," said Craig, handing her a folder. "Along with the revised P-and-A numbers for The Saint. I've placed that issue of Time with Ellen DeGeneres coming out on his desk, and I ran the Q2 Blockbuster sales projections through the fax."

Dianne nodded, scanning the folder. "And The Lost World?"

"Opening Memorial Day. The mock-ups arrived from the printer yesterday. I've scheduled them for his two o'clock."

A younger staff member approached with a slip of paper. "Ms. Kim? Jim Carrey's office confirmed for eleven."

"Craig, what was his mood at breakfast?" Dianne asked, lowering her voice.

"Good but he kept asking when the Titan screening was happening. I said I'd check with Cameron's office."

"Craig is that a Zyn in your mouth? Spit it out.”

Craig spit it into the trash can.

“Thank you,” said Dianne.

"He was talking about Cameron directing with Leonardo DiCaprio starring."

"That was never even announced," Dianne said with a frown. "Does Dr. Imbroglio know?"

Craig shrugged. "I made a note in the log."

Craig arranged the documents in the folder —box office reports, development slates, competitor analyses.

Everything was ready.

Dianne reached over to the cassette player, pressed play and Third Eye Blind’s “Semi Charmed Life” poured out of the tinny speaker.

I want somethin' else

To get me through this

Semi-charmed kinda life

Baby,

Baby,

I want somethin' else

I'm not listenin' when you say,

'Goodbyyyyye'!

She pressed Stop.

"OK everyone, phones in the safe. Welcome to 1997."

Another day at Keystone Pictures had begun.

Dianne walked by the Keystone Film Co. logo on the wall of the waiting room, approached famous actor Jim Carrey and said “Mr. Walsh can see you in about five minutes. May I ask a favor?”

“Sure, Dianne.”

Dianne presented a pair of size 12 Stan Smith tennis shoes.

“I need you to change into these shoes. Your shoes are not period appropriate.”

“Really? They’re pretty generic ….”

“As you know, in this house it is still and always 1997. I will need your phone. And I need you to wear these shoes, which will send no one into paroxysms of cognitive dissonance.”

Jim Carrey, for better or worse, has very small, even delicate feet. But Dianne only had the one pair of period appropriate sneakers, which were size 12 because as she said, “better too big than too small where shoes are concerned.”

Jim handed over his phone and switched into the Stan Smiths.

“In Korea they call such tiny feet burglar’s feet,” she said accusingly.

“Listen, Dianne, is there something I can do to help with all this?”

She turned to him sharply.

“Whatever you do, don’t try to, as you say, ‘help.’ Anything that jars him from the illusion threatens his well being — and even his life. We have crafted this for many years, as you know. So it’s 1997. Liar, Liar is out now and Clinton is the President!”

Dianne turned and let the way toward Jerry’s office and Jim clomped after her.

Jim entered Jerry’s office and took in the familiar sight. A classic fax machine. Scripts and memos on the desk to the right. Oscars arrayed on the walnut bookshelf to the left. The ubiquitous Motel 6 ashtrays since, as Jim vaguely recalled, Jerry’s parents had run Motel 6’s.

And Jerry himself, as always well attired, in a deep blue pinstriped Carroll & Co. suit with a rich silk orange tie. Older now of course, but the same man, and lively.

Jerry rose from his desk chair.

“Jim, you look amazing! Thanks for coming in.”

They shook hands and Jim took in the posters on the far wall — Airplane, In Living Color, Home Alone, The Mask — just a small selection of Jerry’s legendary string of comedy hits.

“Jerry, it’s been too long. Man, look at all these. Good, good times!”

“Fun stuff. Much more to come, old boy, hopefully from our collaboration.”

As Dianne had suggested to Jim, they kept the conversation at a high level. It was a general meeting.

“So what’s next, Jim? How can we get on the Jim Carrey dance card?”

“I’m about to shoot one called The Truman Show with Peter Weir.”

“Love Peter. Good choice no doubt. Love Truman, too!”

“What’s the date, Jerry?”

“What’s the date for what?”

“What is today’s date?”

“April 25, Jim. You writing me a check?”

“What’s the year? I really haven’t been paying much attention of late.”

“Ha. Jim, it’s 1997. You must have been really focused. Is this a bit?”

Jim walked over to the window and surveyed the back lawn, which rolled down out of sight just after the life-sized chess set. He turned back to Jerry.

“It’s a beautiful day out, Jerry. Do you need any help? Is everything ok?”

Jerry looked a bit confused. And at that moment, Dr. Imbroglio burst into the office.

“Mr. Walsh — I’m afraid your next appointment is here early.”

Everyone looked at each other in sequence — Jim at Dr. Imbroglio, Dr. Imbroglio at Jim, accusingly, Jerry at Dr. Imbroglio, and then everyone at Jerry.

“Well. Apologies, Jim. Do call after The Truman Show. I’m very eager to get something on the slate for Keystone.”

Dr. Imbroglio gave Jim an extra stern glance.

“I will, Jerry. And we will.”

Astrid pulled off Crescent Drive on to the white gravel driveway to see her father’s white beaux-arts mansion, which she remembered only vaguely. Closer to the house, the green lawn gave way to a large bed of red roses; the chorus of sprinklers, like automated sparrows, maintained the familiar, rhythmic Beverly Hills chant — “chit-chit-chit-chit-sheeeeee chit-chit-chit-chit-sheeeeee” that sang, she thought, that ‘everything was going to be okay’, in the sprinkler tongue.

A uniformed maid opened the front door as Astrid stopped her car. Astrid got out and thought it could have been any time in the past century — 1925, 1965. Stardust ran through her mind: Beside the garden wall when stars are bright…, perhaps some vestige from the before times, before her mother spirited her away to Ojai and then Uppsala.

“Are these espadrilles ok?” she wondered.

"I'm so glad you called," said Dianne, motioning for her to sit. "But there are complications we need to discuss."

Astrid clutched her screenplay. "I can pose as a writer seeking his mentorship."

Dianne chewed her pen as her expression tightened. "And if he loves your work? If he starts making calls? Ovitz doesn't run CAA anymore. Marty Baum — gone. How do we explain that? Half the studio heads he knows are retired, dead, managers, have been metoo’d, have transitioned, or in any case don’t have landlines. The moment he reaches out to the real world, this ol’ circus tent comes burnin’ down."

"Could it … could it be time?” Astrid suggested.

Dr. Imbroglio poked his head in from his adjacent office, his tall, gaunt frame moving with the slight stoop of someone who'd now spent decades now hunched over playing Minesweeper 1997. He pushed his Lennon wire-rimmed glasses up his long nose with his pinky finger, a habit he'd developed to avoid smudging the lenses.

"Ms. Walsh," he said, his Italian accent still faintly detectable after forty years in America. "With all due respect, you're not qualified to make that assessment. The neurological impact of such a shock—"

As he spoke, his right eyelid twitched slightly.

"And in those twenty-eight years, your father has been stable. His blood pressure, cognitive function, emotional state—all maintained within safe parameters. We've created a sustainable environment."

Dianne gestured to Astrid's outfit. "Those capris alone could trigger questions. And your screenplay references ‘Bumble’ — which didn't exist in ‘97."

"I can change that," Astrid insisted.

"I’m still concerned. If he calls Broder Kurland Webb and discovers the agency no longer exists? When he mentions Keystone Pictures and hears bewilderment on the other end of the line?" Dianne shook her head. "Each of those moments creates a fracture in his reality. His stability is like a full glass from which no water must ever spill. I carefully hold that glass in my hand all day every day like some ill-fated Korean in a Greek myth, as the world tries to shake shake SHAKE …”

Dr. Imbroglio put a soothing hand on Dianne’s shoulder. "Now, now. Cognitive dissonance is not merely uncomfortable in your father's case, Ms. Walsh. It could be catastrophic. The mind creates barriers for protection. Breaking through those barriers—"

Ms. Kim and Dr. Imbroglio looked at Astrid, wordlessly communicating the horror and the fraught tension of 28 years of keeping time.

"So … pretend." Astrid asked.

"Yes," Dr. Imbroglio said firmly, his eyelid twitching more pronounced now. "Precisely that. He can give you notes. He can feel useful. We can intercept any calls, manage any follow-ups. But crossing the stream risks everything."

Astrid stared down at her screenplay. "After all these years, I just wanted to see him. And maybe get some help. In reality."

"I understand," Dianne said, her tone softening slightly. "But you need to decide what matters more - ‘in reality’: getting his help, or keeping him alive."

Astrid stood at the door to her father’s office, script in hand, feeling a slight sweat developing, feeling the need to breathe in, to breathe again through her nose, to breathe again through her mouth, to breathe again …, feeling verklempt, feeling breathless and urgent, wondering what her heart rate would be if she hadn’t had to leave her Apple Watch with that golem, Ms. Kim. It had been 27 years and she could not have a panic attack at this very moment. What year was it? This is not how the scene had played out in her mind. She felt dizzy. And she couldn’t die right now, because she still hadn’t even mastered Wordle much less anything else.

The door burst open from the inside and there was her father but much older. They stared at each other in shock. He said “Ingrid!”

Astrid lost her balance and tried to put her hands against his mouth to silence him and in doing so stumbled into him as he yelled again “Ingrid! Ingrid!”

She stumbled to the floor and he said, “My wife! Are you dead? They said you went out to fetch avocados but. I feel you’ve been gone … so long!”

Astrid heard a brief ringing in her ears but being slumped on the floor helped her recapture her composure.

As Jerry bent over to help her, or kiss her, or to recapture his lost life — it was unclear — Astrid finally spoke, “I’m not your wife. I’m … a writer — with a Friends spec.” And she held out her script in both hands.

Jerry took steps back and stumbled into a seated position on his leather couch.

Ms. Kim entered. “Jerry. This is a young writer from Paradigm. Great promise.”

“It’s clearly Ingrid.”

Dianne said, “Definitely not Ingrid. Definitely Lisa.”

Astrid held back her tears. “I’m Lisa. A writer.”

Jerry gathered himself and straightened his suit as Dianne helped Astrid into a chair.

“OK. Well, sorry about that. Bit of confusion. You look like my wife! But tell me about your script. And don’t be nervous. I’m just a regular guy.”

They were both sweaty, to be honest.

Astrid staring mumbling about her scripts. A Friends spec and a movie spec a woman who unwittingly rents a room from the father she had never met. She talked it through in some detail.

“I must say you have a great sense of drama and at creating moving scenes. Creating turns. That’s what so many writer’s miss — scenes that change and go from A to B to C to D and it’s a new disposition and conflict and mood every time.”

“Thanks so much.”

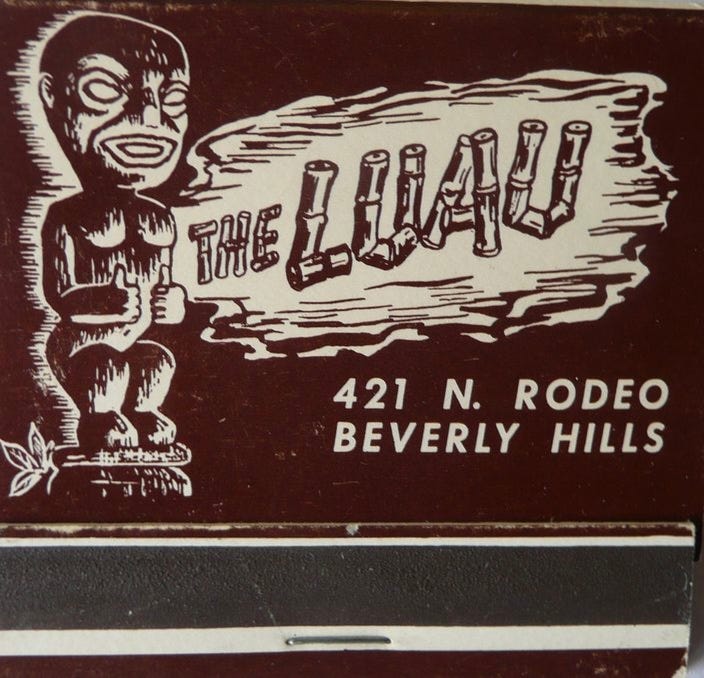

“I’ll read these but I have a crazy idea that you should join the Keystone team. And here’s a spontaneous idea — come to dinner tonight. We’re all going to Chasen’s. Everyone will be there.”

Astrid had a photo of her parents at Chasen’s restaurant, the legendary Hollywood hangout. The picture was one of the few she had of them. Chasen’s had closed years ago though and become a Bristol Farms.

“I’d be happy to come.”

Astrid had had to rush home to get a dress to go to “Chasen’s.” Now that she was caught up on her neglected phone, she wondered whether all the phones were really for the best.

Dianne took her to the end of the kitchen to the garage entrance and said, “Here we are. Remember, this is Chasen’s. In 1997.”

Astrid slipped in.

The atmosphere was instantly warm and bustling, a swirl of besuited, jewelry encrusted bonhomie flavored with sizzling meats, sizzling secrets, and the site of a bartender in the further room making the “Flame of Love” Martini, which indeed threw off a burst of flame with each concoction.

Jerry waved Astrid over from his table, the second red leather booth in the front room decorated with photos of David Chasen and stars who had graced this room in the past.

“Hello, I’m Julius,” said the older tuxedoed European man, evidently the maitre d’.

“Lisa,” said Astrid. “With Mr. Walsh.”

They walked to the table.

Imagine the life I would have led, Astrid thought.

As Astrid approached the table, Jerry yelled out to a passing guest, “Jon, meet Lisa.”

Astrid turned and an intimidating man of her height reached out a hand, “Jon Dolgen.”

“Lisa.”

“That’s my newest, best writer Jon. You gotta move fast in this town!”

Dolgen laughed.

To Lisa, he said “Good luck and welcome.”

To Jerry he said, “I’ll get you next time!”

Astrid sat at the table with Jerry, Diane and Dr. Imbroglio.

A tuxedoed waiter approached, a tall older man with red hair.

“Jerry, what will your new friend be having? Mademoiselle, a martini perhaps?”

“Astrid saw that everyone was having martinis and she smiled “Yes” in assent.

Jerry pointed out the prestigious guests — Ovitz, Diller, Dolgen as mentioned, Sherry Lansing. For a second, Astrid actually wanted to meet all these people before she reminded herself that this was only Disneyland 1997 Chasen’s.

Everyone was there and no one was there.

Jerry expounded and went into his sales pitch for Keystone. He had finished her script that afternoon.

Jerry’s notes, and even Dianne’s, were insightful. He seemed in his element, talking fast, going deep but not to deep for a dinner table and not so detailed that it dwelled on any picayune quibbles. He was skilled at this — making you feel good and promising while also making substantive and helpful points about how the script could improve and what its prospects were.

“So anyway I look forward to moving it down the road. It will take and draft or two but we’ll get there,” Jerry said.

“Oh, fantastic.” Astrid actually felt great. It was 80% like a real development deal, except for the fact that she was in a fake 1997 Chasen’s and that her father wasn’t running a studio anymore and didn’t seem to know that he was her father. Maybe fake pick ups could be a great therapy session back in 2025, she thought.

He asked her where she was from and she demurred. He asked her who her favorite bands were because he liked young people to keep him hip. She struggled with that, but Dianne fed her some suggestions — Third Eye Blind, Jewel, the Notorious B.I.G. She got into it enough to make up a story about a recent Jewel concert.

By the end, as they enjoyed some 1990 Stag’s Leap Cabernet with Hobo Steaks, Jerry was chatting with his “team” and with passing friends. He was in his element.

“I love it here,” Jerry said.

Astrid walked through the east wing of the mansion, an area she had been expressly, though politely, forbidden to enter. The hallways here broke character—modern art hung on the walls, the carpet was new, and an unmistakable aroma of contemporary perfume lingered in the air. So much for 1997, she thought.

She found Dianne's quarters easily enough—double doors with a small brass nameplate. She knocked once, then more urgently when no answer came.

Dianne opened the door just enough to reveal her face. "You shouldn't be here," she said, then relented with a sigh. "What do you want?"

Astrid pushed past her into a room that seemed contemporary. It seemed like a Four Seasons hotel room. Sleek furniture, minimalist design, a massive flat-screen television mounted on the wall. A smartphone lay charging beside a MacBook on a glass desk. "Well," Astrid said, taking it all in. "At least you're living in this century."

Dianne closed the door quietly. "This is my private space."

"I need the truth," Astrid said. "I've been playing along, but I deserve to know how this happened. How he got... like this."

A gentle knock interrupted them. Dianne's face tightened as she opened the door. Astrid felt her breath catch—her mother stood in the hallway.

Ingrid Andersson-Walsh had retained her beauty at sixty; her blonde hair now ash-gray but elegantly styled, her posture still model-perfect, her accent still faintly Swedish despite decades in Los Angeles. "Hello, Dianne," she said with cool formality.

"Ingrid? You can't be here." Dianne's voice had risen half an octave.

"I called her," Astrid said.

"Do you have any idea what seeing her could do to him?" Dianne's fingers gripped the door handle so tightly her knuckles had turned white.

Ingrid swept past her into the room. "What you've been doing to him for twenty-eight years?" Her eyes took in the modern furnishings, the technology, the luxury. "I see you've made yourself comfortable."

Dianne closed the door, her back against it as if to prevent escape. "Do you have any idea what your leaving did to him? You took his daughter and vanished to Sweden."

"After he had his breakdown at the shareholders' meeting? After he threw that chair through the window? After they voted him out?" Each question hung in the air like an accusation.

Astrid felt her stomach tighten. "He threw a chair through a window?"

Her mother turned to her with softened eyes. "You were three. I didn't want you to see him like that." Her gaze hardened again when she looked back at Dianne. "The doctors said six months of rest and therapy. Not twenty-eight years of this... charade."

"He is happy here," Dianne said. "He couldn't face what happened."

"So you built him a prison of 1997," Ingrid said.

"I built him a sanctuary!" Dianne's voice cracked with emotion.

Astrid moved between them. "With yourself as... what? Warden? Caretaker?"

Dianne sank into an armchair. "I kept him alive! When he came out of the coma, and thought he was still running Keystone... Dr. Imbroglio said the shock of reality could kill him."

"And when did Dr. Imbroglio start living in the east wing?" Ingrid asked, gesturing toward a man's cashmere sweater draped over another chair.

The silence that followed felt thick with implication.

"So this whole time..." Astrid began, the truth settling over her like a cold shadow. "This whole elaborate production... it's been about you?"

"No." Dianne looked up, her eyes glistening. "It is about saving him."

"And his money kept paying for it all," Astrid said, nodding toward the luxury surrounding them.

"He's well cared for," Dianne countered. "He's happy."

"He's living a lie!" Astrid's voice rose despite herself.

Dianne looked up, her face suddenly calm. "Who isn’t?"

Astrid felt her mother's hand on her shoulder, steadying her.

"I will be back and I'm going to see him," Ingrid said. "At the party."

Dianne stood quickly. "You can't. After all these years—"

"After all these years," Ingrid cut her off, "it's time."

The lawn shimmered under strings of paper lanterns. The swing band played the hits of 1947. Waiters in crisp white jackets circulated with trays of shrimp cocktail and gin fizzes. The fading light of 2025 lit up a cake decorated with miniature saplings.

The banner strung across the patio read:

KEYSTONE PICTURES ARBOR DAY SOIRÉE

About fifty guests mingled — the carefully maintained illusion of a thriving Hollywood studio party. Fake stars, fake agents, fake executives, some of whom she recognized from last night.

Astrid stood near the edge of the crowd, feeling the unreality of it all press against her lungs. Dianne hovered nearby, tense, tight-lipped, watching everything.

At the microphone, Jerry Walsh beamed. He was in his element — toasting the spirit of Arbor Day, the strength of roots, the power of legacy.

“And here’s to the next generation,” Jerry said, lifting his champagne glass high. “The ones who’ll keep Keystone Pictures green and growing.”

The crowd applauded dutifully.

And then the applause stuttered and died.

One last guest entered from the driveway. The woman who entered was not as tall as she had once been, but she carried herself with the same model’s posture that had caught Jerry’s eye thirty-five years earlier. Her platinum blonde hair was now elegantly silver. Her black gown was classic rather than fashionable, her only jewelry a pair of diamond earrings — a gift from Jerry on their fifth anniversary.

Dianne saw her first.

Her champagne flute slipped from her fingers and shattered on the patio stones.

“No,” Dianne breathed. “No, no, no…”

The guests, uncertain, began to part, creating an invisible corridor.

Jerry’s hand tightened on the microphone stand.

He stared, wide-eyed, as Ingrid — Maja — walked slowly toward him.

“Maja?” he croaked, the microphone amplifying the sudden roughness in his voice.

Ingrid kept walking, calm, composed, her eyes locked on his.

“Hello, Jerry,” she said, her voice still carrying that slight Swedish accent that had once disarmed half of Hollywood.

Jerry stepped down from the stage like a sleepwalker.

Dianne pushed through the crowd, trying to reach him, but Jerry didn’t even see her.

He reached Ingrid and, trembling, raised a hand to her cheek.

“You’re real,” he whispered.

“I’m real,” Ingrid said.

Jerry shut his eyes. A long, rattling breath escaped his chest.

When he opened them again, he turned slowly toward the swing band, who had frozen mid-song.

“Play ‘I’ll Be Seeing You,’” he said.

There was a beat of confusion. Then the soft, mournful notes began — tentatively, then stronger — drifting over the stunned party.

Jerry took Ingrid’s hand, pulled her gently onto the patio, and they began to dance.

Astrid watched from the shadows, her throat tight.

They moved slowly and gracefully. One could almost see the swirl of memories surrounding them and the dance floor.

The lanterns swayed above them. The roses nodded in the breeze. The garden was suspended in an impossible moment, the moment that was finally here.

When the song ended, Jerry held on for just a beat longer before stepping back.

A tear ran down his face.

He turned, scanning the crowd, seeing it truly for the first time — the actors, the perfect scripts, the endless façade.

His gaze settled on Astrid.

“You’re not Lisa from Paradigm,” he said.

Astrid stepped forward, feeling every eye on her.

“No,” she said. “I’m your daughter.”

Jerry blinked, dazed.

“The script you showed me… is it real? Is it available?”

“It’s real,” Astrid said. “And it’s available.”

Jerry laughed. “Thank God!”

A ripple of uncomfortable chuckles passed through the crowd.

Jerry turned back to Ingrid. His voice steadied.

“Obviously, I have to ask — what year is it?" he asked, his voice clear and strong.

Dianne stepped forward. "It's 1997, Jerry. April 25th, 1997. Please—"

But Jerry's focus remained on Ingrid. "Tell me the truth."

"It's 2025," Ingrid said. "It's been twenty-eight years since your stroke."

Jerry nodded slowly, as if confirming something he'd long suspected. He turned to the remaining guests. "Thank you all for coming. The party is over."

The backyard emptied quickly, leaving only Jerry, Ingrid, Astrid, Dianne, and Dr. Imbroglio, who hovered anxiously near the door.

"Twenty-eight years," Jerry said, not a question but a statement of fact. "I've been living in 1997 for twenty-eight years."

"You had a stroke," Dianne said, her voice breaking. "After the board meeting when they voted you out. You threw a chair through a window. When you woke up in the hospital, you thought you were still running Keystone. The doctors said any shock could trigger another stroke, possibly fatal."

"So you built all this," Jerry gestured to Dianne. "This elaborate fiction."

"It was supposed to be temporary," Dianne said. "Just until you were stronger."

"And then it became permanent," Jerry finished.

He turned to Ingrid. "And you took our daughter to Sweden."

"I couldn't let her grow up in Hollywood," Ingrid said. "I thought you'd recover. I thought you'd come find us."

Jerry closed his eyes briefly. "I remember searching for you... in 1997."

Silence stretched between them, heavy with decades of lost time.

Astrid opened her mouth, but Jerry spoke first, his voice low and bewildered.

“Before the stroke,” he said. “It was the emails.”

He turned slightly, as if seeing the ghosts gathering around him.

“They hacked Keystone. The North Koreans, of all people. They were looking for secrets — secret movie plans about Asia, whatever — and instead they found me. Calling Rosie O’Donnell a shaved bear and saying that the marketing people at Keystone were mentally retarded.”

His voice cracked on the words.

Ingrid said nothing. Dianne looked stricken.

“They leaked it to get to me so I wouldn’t make the Kim Jung-Il movie. The trades picked it up. Overnight, I was a punchline.”

He let out a dry, brittle laugh.

“Savages Keystone. Savages Rosie.”

He shook his head. “They fired me the next day. Voted me out. I still had the chair in my hand when they made it official.”

Astrid stared at him, not sure if she should move closer or stay perfectly still.

“I thought maybe if I showed them — scared them — they’d remember what mattered. But all they saw was a crazy man throwing furniture.”

He paused.

“And then you left,” he said, looking at Ingrid. “Took Astrid. Took the only real thing I had left.”

He pressed his hand lightly to his chest, as if remembering the slow collapse of his own heart.

“And then,” he finished, “I woke up here.”

He gestured faintly at the tented lights, the lingering music, the vast and empty night.

Astrid stepped forward, carefully, like approaching a wounded animal.

“You don’t have to stay,” she said. “Come with us. It’s not too late.”

Ingrid reached for his hand, not pleading, just offering.

“We can go home,” she said.

Jerry looked at them — really looked. His wife, older but still radiant. His daughter, grown, a stranger and not a stranger.

The real world stretched out just beyond the driveway, waiting.

He took a step toward them. Then another.

For a terrible, hopeful moment, Astrid thought he might actually cross the threshold.

But then he stopped.

“We can be together,” he said. Looking at Ingrid.

Ingrid said, “You can come with us, Jerry. We’ll help you. But I can’t stay with you. My life… it moved on.”

His gaze drifted back toward the house, the red booths, the paper lanterns still swaying in the warm spring breeze.

Jerry smiled — a small, broken, beautiful smile.

“If you’re not going to be with me,” he said quietly, “I’d rather you be just out getting avocados. Always about to return.”

Jerry turned back toward the house without waiting for an answer.

The lights from the party flickered softly against the arbor trees, casting long, wavering shadows across the lawn.

Astrid watched him go — a figure retreating into the past, smaller with every step, until he disappeared into the golden haze of the old world.

Astrid stood there for a moment longer, not crying, not moving, feeling the stillness settle around her like mist.

She would never see him again — not really. But he would always be waiting, forever, around the corner, where the avocados were.

Brilliant! Thank you, Roy.

Choosing comfort and the familiar over taking risks. Recasting and remaking what worked in the hopes it would work again. All the while your family and your audience moves away, and further away…

Freshwater like fresh ideas abounds at the bottom of the well.

I watched Bergman’s “The Silence” in a full movie theater on Thursday. And got to live in 1963 and every year that came before and every year that has followed.

Onwards!